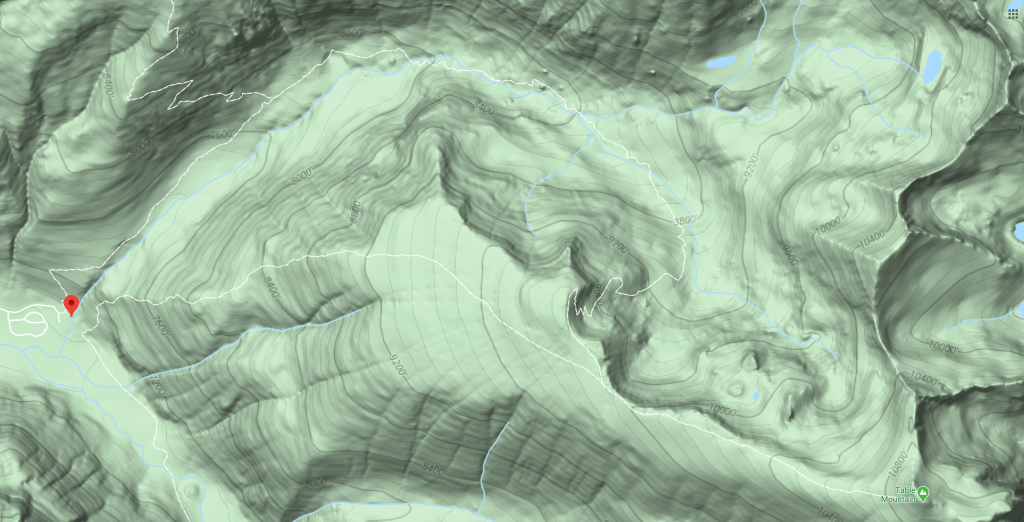

The peak of Table Mountain is a prominent rock about 50 yards long that, from 11,100 feet above sea level, offers stunning views of the Grand Teton and surrounding canyons. I figured the 11-mile loop would be a great leg workout. But I grossly underestimated the effect that altitude would play on this excursion.

The trails start at 6,800 feet. I opted to ascend via the 4-mile-long Face Trail. The first mile covers over 2,000 feet in altitude, so it’s like climbing a mile-long flight of stairs. I could tell the air was thinning as the trail leveled out above 9,000 feet and I was still breathing heavily to maintain a decent walking pace along terrain that would normally constitute a light stroll.

As altitude increases air density decreases. The most direct effect of that on physical performance is a reduction in available oxygen (“hypoxia”) as the mass of air in a fixed volume (your lungs, for example) decreases. At 9,000 feet above sea level (ASL) air density is 75% of a sea-level atmosphere. By 11,000 feet it falls to 70%. I.e., the amount of oxygen available in each breath is only 70% of that available at sea level.

At 10,500 feet, the quarter mile approach to the peak of Table Mountain (“The Rock”) begins to increase in slope and finishes with a nearly vertical climb up the 50-foot face to the top. This is when the effects of hypoxia slammed me. I began breathing as deep and fast as possible, as if I was running a race at 100%. But I was only able to maintain a slow walking pace up the slope. As it steepened I had to make increasingly frequent stops to catch my breath. Then I had to sit on the ground to catch my breath each time. I would get up determined to take 20 … then just 10 more steps, but I scarcely had enough oxygen to count at the same time.

With only hundreds of feet left to traverse, I actually began to wonder if I would be able to summit The Rock. From my flying days I had a notion that hypoxia didn’t start to affect people in decent shape until at least 14,000 feet. Maybe that’s for altitude sickness … or people just sitting in unpressurized cockpits. Evidently aerobic capacity takes a huge hit at lower altitudes: During my breaks as the incline grew past 25 degrees I began to look at the other hikers. There were a lot of people bunched up on this last segment, and a lot of them were stopping frequently, sitting down or leaning on trekking poles. This included people who looked like serious athletes. In contrast, some of the more elderly and apparently out-of-shape hikers were able to plod onward without stopping. Altitude acclimation is a serious thing!

On top of The Rock it took a few minutes to fully catch my breath. Climbing back down was no problem. I maintained a normal breathing rate while virtually skipping down the same grades that took me straight to the wall of my aerobic capacity when ascending.