For years, programming something new followed a predictable, exhausting rhythm: write some code, hit a wall, and then disappear into a forest of documentation and StackOverflow tabs to find the trick to get it working. In 2025, that era ended for me.

Today, AI code assistants take so much drudgery out of development and debugging that the work has become mostly gratifying and rarely frustrating — the opposite of how programming was in the Before Times.

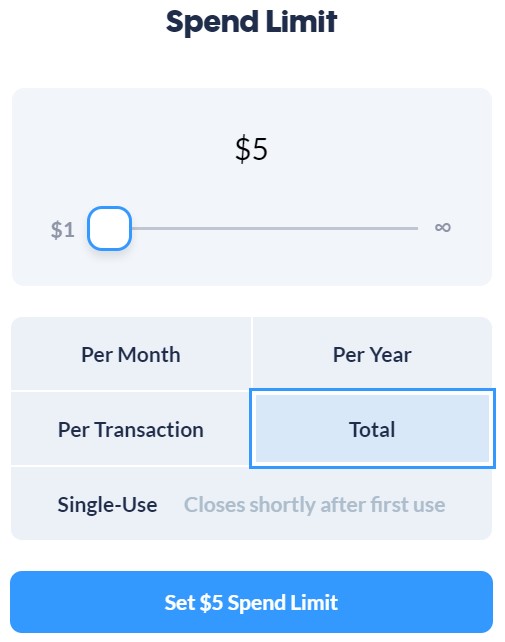

Between my work and my side interests, I often feel like I live in Visual Studio Code (VSCode — a popular open-source development environment). Early in 2025 I subscribed to GitHub Copilot, which integrates AI coding assistants into VSCode. At $10/month it’s a phenomenal bargain that offers software developers an easy way to loop in the latest models from OpenAI, Google, and Anthropic. Now when I’m trying something new (like this little project I did for fun) I can mostly stay in VSCode and work with an AI assistant that has mastered all of the documentation.

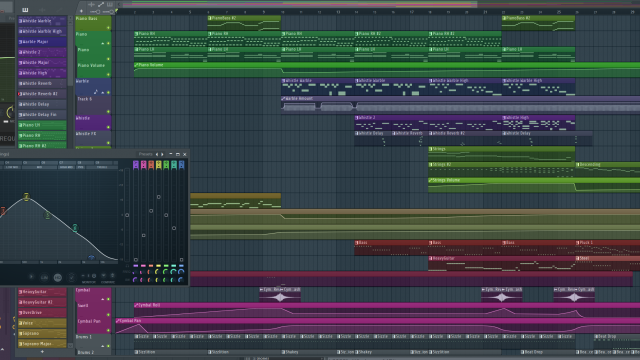

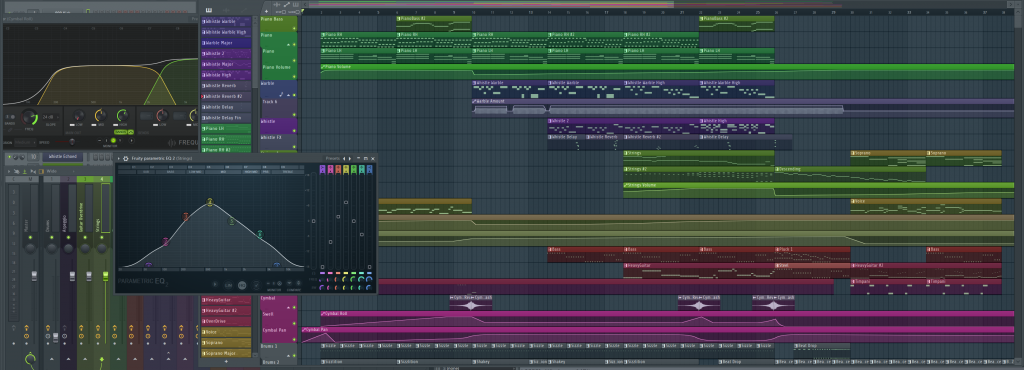

As mentioned elsewhere, my most significant side project in 2025 was helping Ukrainians develop an open-source ballistic calculator (pyballistic) in Python and Cython. I polished that off at the end of September. By that point I had begun to spend more time with Github Copilot, and the capabilities of its latest models gave me enough confidence and support to tackle what would have previously been an absurdly ambitious project for my day job: an Excel Real-Time Data (RTD) server for the Interactive Brokers API. (This RTD server feeds live market data, positions, and orders directly into Excel using native Excel formulas.) After two months of working seven days a week on that, I had a beautiful piece of software so solid (and validated every build by over 800 unit tests) that I had begun to use it in live trading operations.

Early Childhood Development

Watching these models mature over the last year has been like watching a child grow up.

Tell a child, “Clean your room.” First they’ll spend more time arguing than it would take to just do it. When they finally declare the task “done,” you might find a few toys picked up but most of the mess still there. Emphasize that “clean your room” means everything and you might find the floor clean but everything shoved under the bed.

Claude v3 was notorious for hacking shortcuts. Ask it to fix a failing test and it might just replace the test logic with a “return true;” statement. Claude v3.5 wouldn’t be so brazen, but it was still prone to hack the example rather than the task. GPT-4 and Gemini v2 would enthusiastically announce completion without checking their work. Like the child who picks up two toys and concludes that his room must be clean, even though the mess is visible from outside the door.

The teens came quickly: Claude v3.7 and its contemporaries would often spend more effort arguing that its failure was actually success than it would have taken to do the work correctly.

More recent models have become more likely to keep checking and working until they succeed. Performance of the latest models is still wildly variable: a model that astonishes me with its apparent skill one day may choke on something relatively simple the next. But they are getting more consistent. And they are definitely getting more intelligent.

What is intelligence? It becomes easy to see when you’re doing hard work with different models. One of the neat things about Copilot is that you can choose to watch the model at work. They all think “out loud,” meaning you can read their chain of thought to understand how and why they do things. When it’s not having an off day, Claude Opus is intelligent. Given a problem:

- It can more reliably identify what matters.

- It has a better sense of what to look at and what to ignore.

- It produces better assessments of what’s possible and makes better plans to get there.

- It knows when to persist and when to change directions.

These are some of the things that separate a junior developer from a more experienced one. They are also qualities that characterize more intelligent people.

Let me show you. Have you ever wondered what it’s like debugging software? Well, debugging is one thing the newer models can usually do as well as a good human programmer. In fact, they can do it better because they can run the process faster and interact with the code more directly. Below I pasted a transcript of Claude working to find and fix a tricky bug in my RTD server. This could just as well have been a transcript of my thoughts if I had to debug it. But whereas this would have been a draining hour+ distraction for me, the Claude instance cranked this out in minutes.

Continue reading “Coding Agents Grow Up”